Fee for service vs Value based Healthcare

For the past 50 years, healthcare in America has worked through a fee-for service system - in that providers get compensated for the volume of consultations, tests, and procedures they do. Initially, there weren’t too many high volume, costly procedures. But as more non-invasive diagnostic tests (CT, MRI, PET), minimally invasive procedures (laparoscopic, robotic, endoscopy, interventional) and chronic care treatments (ex: dialysis) were performed, the cost to the system increased.

As this system matured, it has become more and more important for healthcare to base compensation on value vs volume. How is value determined? Simplistically, value = quality/cost; therefore, the higher the quality and lower the cost, the higher the value.

Historically, quality in healthcare has been tough to measure. Patients are complex with varying degrees of comorbidities & social determinants of health dictating the quality of care. However, as the volume of care has gone up, an increasing level of payment models are centered around quality metrics. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has created several programs throughout the years to move healthcare from a fee-for-service model to a value-based care model.

MIPS Payment in Healthcare

The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is one of two tracks under the Quality Payment Program, which moves Medicare providers to a performance-based payment system. MIPS streamlines three historical Medicare programs, the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-based Payment Modifier (VM) Program and the Medicare Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Program (Meaningful Use), into a single payment program₁.

There are four performance categories that make up the MIPS score (total of 100) - which dictate the payment adjustment. The 4 categories are: Quality (45%), Promoting Interoperability (PI) (25%) , Improvement Activities (15%), & Cost (15%). Quality is determined based on performance measures created by CMS, medical professional and stakeholder groups. Providers pick the six measures of performance, including at least one outcome measure, that best fit their practice₂. Additionally, practices will need to report performance data for 70% of the patients who qualify for each measure.

There are currently 219 performance measures (across all specialities) that providers can choose from₃. There are 7 types of performance metrics: Efficiency, Intermediate Outcome, Outcome, Patient Engagement Experience, patient reported outcome, process and structure.

For MIPS reporting, the max downward and upward adjustment increases yearly. In 2019 the total adjustment range was -4% to +22% and in 2025 the total adjustment range will be -9% to +27%. Given the >30% range in payments, appropriate reporting of MIPS metrics is critical for the current & future revenue.

QCDR

To meet the growing demand of developing and reporting quality outcomes, CMS has approved the use of specialty-specific Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDR) to be used as a reporting mechanism. QCDRs allow providers to report on measures that are meaningful to their speciality practice and the registries collect medical or clinical data for the purposes of patient/disease tracking to foster improvement in the quality of care provided.

GIQuIC

The Gastroenterology Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQuIC) is a clinical benchmarking tool that has been used in gastroenterology to help facilitate endoscopics’ documentation of quality reporting metrics since 2010. Starting in 2019, the GiQuIC has been approved as a QCDR for MIPS reporting.

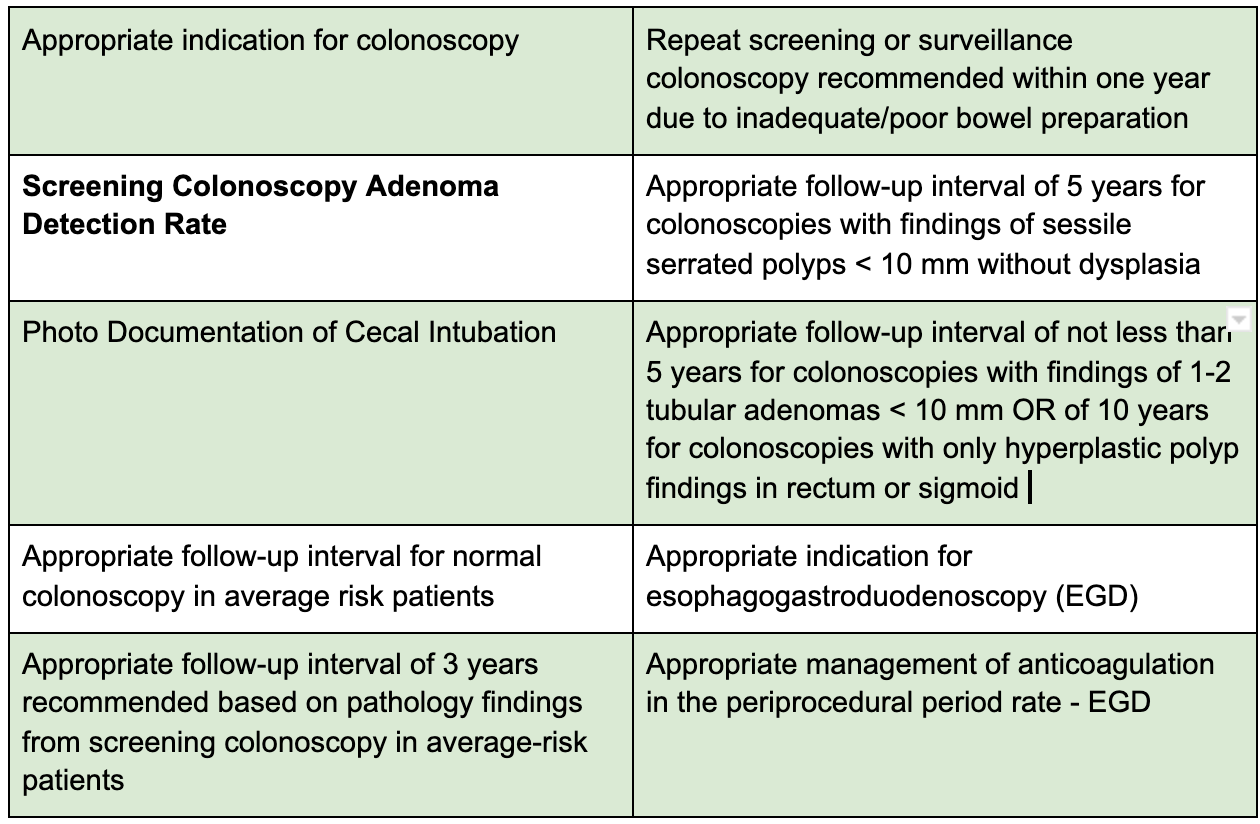

The GIQuIC QCDR includes 10 measures (8 colonoscopic and 2 Esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD]).

The measures are shown below:

Of the 10 metrics, the screening colonoscopy adenoma detection rate is the only metric that is an outcome measure.

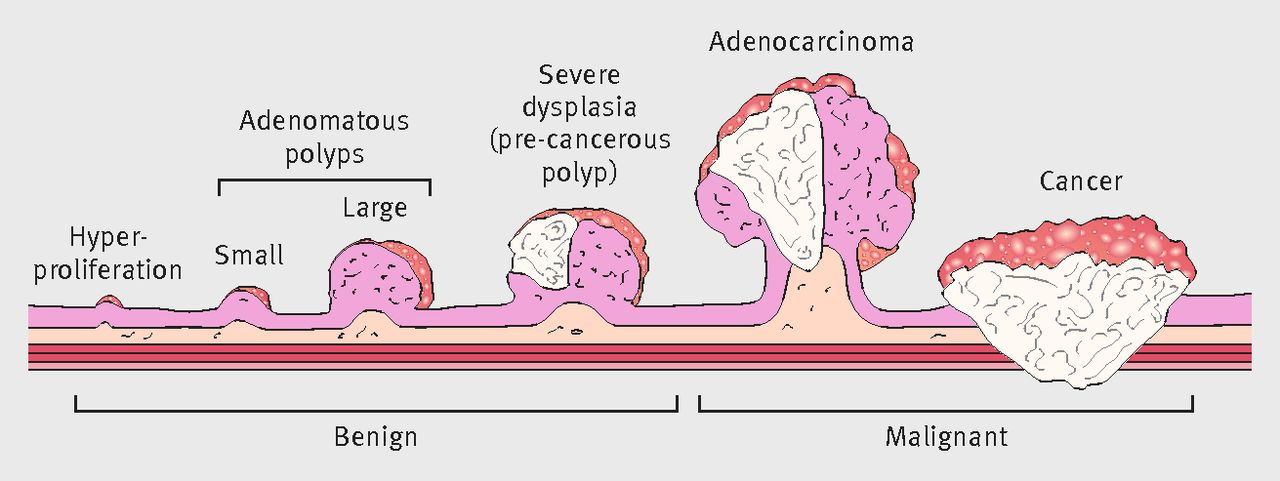

Adenoma Detection Rate

The adenoma detection rate (ADR) is defined as the proportion of patients undergoing colonoscopy in whom an adenoma or colorectal cancer is found. High ADR is associated with a significant reduction in colorectal cancer risk. Each 1.0% increase in the ADR is associated with a 3% decrease in the risk of cancer₄. However, virtually all studies on this subject have found marked variation in ADRs among physicians. Therefore, it is a very important metric to evaluate the endoscopists quality of care and utilize this metric as a baseline quality reporting tool to assess and improve performance across the health system.

Although ADR is a key metric for evaluation, it is not as easily reported as other measures because of 2 factors: time-delay & interdisciplinary coordination of results. The ADR can only be determined after the fact - once the results are obtained from the pathologists 1-2 weeks after the screening colonoscopies are completed.

Furthermore, reports are often generated in a non-standardized format and are not always integrated into electronic health records (scanned/faxed reports). Even if records are integrated into the electronic health record, the data may not be in a form that is easily extractable for reporting purposes. Given these challenges, the ADR is underreported nationwide. However, without reporting this important metric, gastroenterologists would not be able to participate in effective MIPS reporting - and may not be eligible for the +27% performance adjustment while risking a -9% decrease in reimbursement.

NLP & OCR Workflow

For this reason, natural language processing (NLP) & optical character recognition (OCR) tools have been used to obtain relevant clinical information from scanned/faxed colonoscopy & pathology reports.

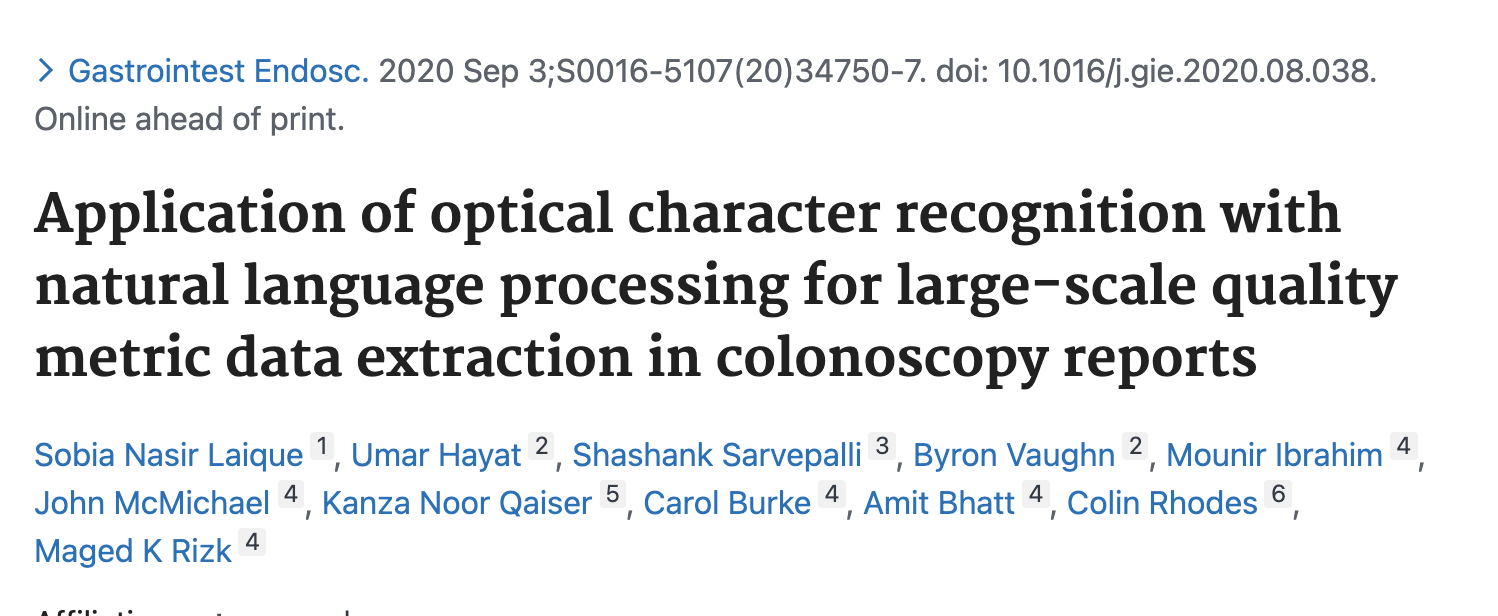

Recently, a study from the Cleveland Clinic, University of Minnesota, and eHealth Technologies evaluated this technology against 2 manual reviewers and found that their tool (OCR + NLP) was able to accurately obtain 99% of all desired variables. In particular, when looking for the specific type of adenoma detected, the accuracy was between 95.8% & 99.3%.

The authors estimate their NLP algorithm now takes under 30 minutes to extract data on all colonoscopy procedures ever done at their institution since the introduction of EHRs. Contrasting this with manual data collection, both authors who manually extracted the data took about 6 to 8 minutes per patient, which equates to a total of 160 man-hours for annotating data from fewer than 600 patients₅.

Next Steps

As of 2017, 19 million colonoscopies were performed annually₆. Unfortunately, the information needed to assess colonoscopy examination quality is often embedded in non-standardized colonoscopy procedure reports of varying formats within electronic health records (EHRs), requiring time-consuming and costly manual data extraction for accurate reporting. The lack of tools that allow error-free extraction of high-quality information has remained a major obstacle in navigating these unstructured data sources to improve the efficiency and accuracy of patient care₇.

From our conversations with practicing gastroenterologists, even though these NLP + OCR solutions have been described in the literature for several years, there is a huge gap in terms of applicable tools at an enterprise level. Additionally, internal IT workflow may be difficult given the level of interdepartmental coordination and specialized NLP + OCR coding skillsets required. Given this landscape, we believe a customizable external solution that interacts directly with the various EHRs, utilizes NLP + OCR to extract data, adjudicates the various data sources against each other, and provides the raw data & insights necessary for quality reporting & quality improvement would be ideal - ultimately optimizing a GI practice’s adjustment factor and revenue.

References

1. https://www.practicefusion.com/quality-payment-program/what-is-mips/

2. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

3. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures?tab=qualityMeasures&py=2020

4. Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, et al. Adenoma Detection Rate and Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Death. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(14):1298-306.

5. Laique SN, Hayat U, Sarvepalli S, Vaughn B, Ibrahim M, McMichael J, et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020.

7. Laique SN, Hayat U, Sarvepalli S, Vaughn B, Ibrahim M, McMichael J, et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020.